If there’s one thing in the entire world that I want to share with you, it’s this breakthrough I had about shame. I want to tell you about it for two reasons. The first reason is that it improved my life. And I’m not the only one. Shame is the boogieman with a million different names in most self-help and personal betterment schemes. Overcoming it is the substance of pretty much every inspirational quote. It’s in the words and deeds of anyone who has pioneered anything new, revolutionary, or counterculture. It is so universal in fact, that it’s become the kind of advice you just sort of nod your head along with and think, “Yeah, yeah, I know that”. But the truth is, you probably don’t. Because it’s not something that you can just know in theory, it’s a breakthrough that you have to have. You need to experience it, to really get it.

And if that sounds pretentious, then you should know that the second reason I want to tell you all this is because I want you to like me. Incidentally, this second reason is proof of the first. Because in spite of my so-called “breakthrough”, and all that I’ve learned about shame over the last few years of obsessively studying, thinking, and talking people’s ears off about it, so much of what I do is still affected by shame. At this point, I’d like to believe I’ve become a shame expert, but the truth is I have zero credentials to be telling you any of this. I’m not a doctor, or a psychologist, or a psychic, so take everything I say with a big grain of salt. My only real qualification is that I have a lot of experience with shame (unfortunately). For example, even though I am completely aware of it, right at this very moment shame is still pressuring me, not unsuccessfully, to impress you, amuse you, and please you, promising in return nothing less than the sweet sweet validation I might feel from your potential approval of me. That’s how powerful and omnipresent shame is and why we could all benefit from being more conscious of the ways in which it is shaping our lives.

* * *

In its most basic form, shame is the unbearable feeling that you are different, bad, and alone. And whether we want to admit it or not, it is something we all experience. Celebrated shame and vulnerability researcher, author, guru, and my personal lady crush, Dr. Brené Brown, says of shame, “No one wants to talk about it. And the less you talk about it, the more you have it.” Why? Because shame is an external feeling that exists only in relation to other people. Our shame is fuelled by their perceived disrespect, scorn, ridicule, or judgment of us. It is based on the subconscious belief that these external opinions create a kind of collective “truth” about us that is actually real. And so we conceal our shame for fear that exposing it will only affirm these potentially negative external opinions. The assumption being that if we feel shame, it must be because we have something we should be ashamed of. But the truth is, everyone naturally has shame. It’s an instinct that cannot be avoided. So all it really reveals is: you are human.

That said, it’s literally shame’s job to scare the crap out of you. Shame is a social instinct that pressures us to cooperate with other people, to get along, to “fit in” through negative reinforcement. As such, shame manifests as the excruciating, stomach-churning dread that we just don’t belong, because we’ve either done something or experienced something or just innately are something that is objectively wrong and/or any of the almost endless list of shame words we have in our vocabulary: flawed, disgraceful, inferior, dishonourable, weak, disgusting, inadequate, ugly, incompetent, dirty, pathetic, deficient, sullied, aberrant, impure, perverted, monstrous, inhuman, sick, unholy, evil, worthless and, especially, unlovable. I think the ultimate fear of shame, and perhaps the ultimate fear of our entire lives, is that somehow we inherently don’t deserve to be loved. It’s like we’re just buying time until everyone else figures that out, at which point we assume we will be — perhaps even should be — exiled by our loved ones and cast out of society to die alone — wretched, lesser, bad bad bad. In this respect, shame is one of the most powerful and terrifying emotions we have. Brené Brown calls it “the master emotion”.

But in my experience, shame is much more complicated than just an emotion. Most people assume they don’t have a problem with shame because most of us don’t actually feel shame all that often. Shame itself is so abhorrent, that it is the subconscious fear of shame that really motivates us day-to-day. We fear that if we actually do feel shame directly, it will be too late to recover. So we’ve built up all these elaborate unconscious defense mechanisms to avoid acknowledging shame’s very existence, but ironically it is these defenses themselves that do the most damage.

In the aftermath of a terrorist attack, when politicians are trying to legalize mass surveillance and warrantless body cavity searches, people often protest, “If we give up our rights, the terrorists win.” Yes, in this analogy shame is now terrorism in that it’s less about the actual shame attacks than it is about all the ways that we limit ourselves for fear of possibly feeling shame. This is how shame wins, by controlling us indirectly and holding us back from our full potential. This control amounts to a kind of ideology that we buy into — a series of troubling beliefs with roots that go so much deeper than the dictionary definition. It’s these unconscious beliefs surrounding shame that really interest me.

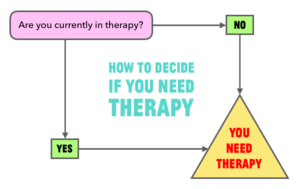

So where to start? Therapy! That’s where to start. If you’re not sure whether therapy is right for you, consult this handy flowchart:

If you aren’t in therapy, go to therapy. If you are in therapy, stay in therapy. What could be a better investment than getting a masters degree in yourself? There’s good affordable therapy out there, there’s online therapy, there are even therapy apps now — so there really is no excuse. As I’ve said before, childhood is a cult. You are literally an empty vessel that gets brainwashed by your parents and society, the chief tool of which is shame. Therapy is a way to start deprogramming yourself from that cult. It doesn’t even necessarily matter how “good” your therapist is either, because you’re the one who has to do all the work anyway. Which isn’t even that hard. Just talk honestly about your shit, have a few mind-blowing realizations, and remember to take notes!

It wasn’t until I finally started taking notes in therapy that I had what I call my “shame breakthrough”. As I looked back over my years of low-level discontent, nagging anxiety, desperation for attention, and chronic people pleasing, I began to uncover a consistent thread running through it all. There was something under the surface dragging everything down, like a black hole, and I eventually discovered there was a name for it: shame. I realized that my view of the world was constructed on an invisible foundation of shame and therefore many of my motivations and core beliefs, especially my assumptions about what made one a “good” or “successful” or “lovable” person, were totally wrong.

I want to make it clear that these weren’t beliefs that I chose or endorsed. I’m talking about dogma, beliefs that I picked up unconsciously from my culture and my family at a young age and basically just took for granted as “the facts of life”. We usually think of dogma as something reserved for the fundamentalist religious set, but we all have dogmatic beliefs ingrained in us during the cult of childhood that we likely aren’t even aware of. I certainly wasn’t. It took a few years of therapy, introspection, and reverse engineering my own behaviour to finally admit to myself what my core dogmatic beliefs actually were.

So what were they? Well, it’s kind of embarrassing and kind of cliché, but from what I can piece together it seems that I believed human beings were not innately worthy of love, or even respect for that matter. I know the word “love” is so generalized and overused that it’s kind of become a meaningless catchall, but in this case, I basically just mean positive human connection. A sense of belonging. The feeling that other people might accept you, approve of you, respect you, like you, and want you around. Incidentally, this need for human connection and love is completely natural and fundamental to our species. Like shame, it’s another social instinct, but one that encourages us to cooperate with other people through positive reinforcement. We are born to seek love, which makes it all the more disturbing that I didn’t think it was something we naturally had a right to.

With billions of people on the planet, I thought that to be truly worthy of this kind of love and respect, you had to be a human with value. That is to say, you had to prove that you had something extra that made you worth loving. Something that made you special, or better than all the others. To gain that extra value, I thought you needed to publicly perform some impressive feats in order to earn a degree of “success” or even better, fame. Because fame, it seemed to me, was the ironclad stamp of public approval. A way to feel worthy of love and respect from anyone and everyone. Because even if some random jerks didn’t like you, they couldn’t ignore your fame as if it was objective “proof” of your universal value, worth, and lovability.

But as with all things shame related, it gets even weirder. If you had asked me at the time if I believed in this “fame-as-worthiness” ideology, I would have said, “Absolutely not, that’s totally superficial and actually kind of pathetic.” And the worst part is, I would have thought I was being honest! That’s because in shame, perception trumps reality. To quote Brené Brown again (and not for the last time), “Shame is how we see ourselves through other people’s eyes.” Because shame is external, it’s all about what people think of us, not what’s actually authentic or true. Right now, for example, I want you to like me. But I’m also savvy enough to know that you won’t like me if it’s too obvious that I am trying to make you like me. So instead of outright asking you to like me, I’ve cleverly disguised it as a 7-part shame manifesto that no one wanted (but everyone needed). In shame, much of what you do gets cloaked under the guise of its opposite, even in your own head. Especially in your own head.

A perfect example of this is the so-called “humblebrag” on social media, as coined and collected by the late comedian Harris Wittels. @jaredleto tweets:

Just won GQ style award in Germany. Obviously they made a mistake. I wonder how long till they come take it back. 😉 #andthewinnerisWHOOPS!

— JARED LETO (@JaredLeto) October 28, 2011

Does Jared Leto actually think this award was a mistake? No. So what exactly is the purpose of this tweet? It’s a faux-modest announcement that he won an award for dressing well in the least stylish nation in the world. Granted, we’ve all engaged in slightly less obnoxious versions of this behaviour. While we kind of know we’re bragging, we mostly think we’re joking. But actually deep down we still really do want to communicate that we are important and/or talented but also that we are self-aware and/or funny (or whatever combination of values we subconsciously think will lead to respect and lovability).

If you look beyond all the clever, self-effacing captions at the careful image-crafting happening on social media you’ll see that I’m clearly not the only person harbouring this ideology of “fame-as-worthiness”. It’s basically ingrained in Western society. And if you break this dogma down even further, it reveals some disturbing assumptions about the world:

- First, this belief system implies that some human lives have more value than others.

- Second, it insinuates that your purpose in life is thus to prove to people that you have the highest value possible.

- Third, it assumes that your value is therefore determined by the opinions of other people. Their approval, admiration, respect, fondness, etc, literally establish your worth and lovability as a human being.

Under this worldview, you are essentially a human Instagram post — your value is based on the number of “likes” that you accrue, and from whom. If you don’t get any likes, or if you lose them, that means you are literally worthless and unlovable. This puts complete power over your life into the hands of other people, be it your parents, your family, your Facebook friends, your real friends, your neighbours, your partner, your pastor, your boss, your coworkers, your Twitter followers, your politicians, your judges, your lawmakers, even strangers. I was unconsciously allowing all these other people to dictate not only my personal worth as a human being but also — by proxy — my opinions, my morals, my values, my successes, my failures, my limits, my everything. These other people were essentially dictating my entire reality! And it was all held together by the terrible fear that these same people might otherwise disapprove of or reject me. And that is the fear of shame.

Part 2: What Shame Isn’t, here!